Exploring a Late Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystem: The Almond Formation, Southwestern Wyoming

What: This Gateway project will investigate the sedimentology and taphonomy of a newly discovered fossil assemblage in the Campanian-Maastrichtian Almond Formation of southwestern Wyoming. Students will develop skills in identifying vertebrate fossils, from tiny minnows and amphibians to crocodiles, mammals, and dinosaurs.

When: June 10-July 14, 2026

Where: Macalester College, Saint Paul, Minnesota (home base); Southwestern Wyoming (field area); GSA Annual Meeting in Denver, Colorado (11-14 October 2026)

Who: Ten students, a peer mentor, and project directors Dr. Raymond Rogers and Dr. Kristi Curry Rogers (Macalester College).

Prerequisites: Because this experience is a Gateway Project for rising sophomores, there are no specific coursework prerequisites.

Expectations and Obligations:

1. Participation in all project-related work during the summer (5 weeks)

2. Submission of an abstract (individual or in groups) and presentation of a paper (poster or talk) at the Geological Society of America Meeting in Denver in October, 2026 (all expenses covered).

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

This project builds upon two previous Gateway projects from 2019 and 2022 (Roat et al 2019; Zimmermann et al 2019; Mendez-Curbello et al. 2022; Noonan et al 2022). In those projects, Gateway students investigated the taphonomy and paleoecology of vertebrate microfossil bonebeds (VMBs) – concentrated deposits of small, disarticulated, and taxonomically diverse vertebrate remains (Figure 1). VMBs are common in Mesozoic and Cenozoic terrestrial records and are critical for recovering small-bodied taxa that are otherwise rarely preserved. They are the richest source of Mesozoic mammalian fossils (e.g., Simpson 1926; Sloan & Van Valen 1965; Sloan 1969; Sahni 1972; Archibald 1982; Lillegraven & Eberle 1999) and have been widely used to reconstruct the paleoecology of ancient vertebrate communities (e.g., Estes 1964, 1976; Estes & Berberian 1970; Dodson 1987; Bryant 1989; Brinkman 1990; Peng et al. 2001; Sankey 2001; Jamniczky et al. 2003; Brinkman et al. 2004, 2007; Carrano & Velez-Juarbe 2006; Demar & Breithaupt 2006; Sankey & Baszio 2008).

Figure 1: Collections from Turtle Hill locality, Almond Formation, Wyoming. A) Sample housed at Macalester College. The sample has been sieved and is ready to be sorted and studied by Keck Gateway students. Each plastic bin (n=38) preserves several hundred small vertebrate fossils. B) In this view abundant bones and teeth (brown) and amber are mixed with rock fragments. Scale bar is 1 cm. C, D) Close-up views of identifiable specimens recovered from Turtle Hill locality. Specimens figured include fish teeth, fish fin bases, scales, an amphibian jaw fragment, and a tiny phalanx. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Most studies of VMBs have emphasized taxonomic and faunal data, with only secondary attention to formative processes. Consequently, detailed analyses of sedimentology and taphonomic history are rare (but see Rogers and Brady, 2010; Rogers et al., 2017; Curry Rogers & Rogers, 2024). The mechanisms driving the accumulation of vertebrate skeletal material in VMBs therefore remain poorly understood, and existing hypotheses have been explicitly tested in only a few formations. Moreover, many studies of VMB-derived collections have been shaped by assumptions that biotic (selective predation) and abiotic (hydrodynamic transport, sorting) processes bias accumulation (e.g., Dodson 1971; Wolff 1973; Maas 1985; Koster 1987; Wood et al. 1988; Blob & Fiorillo 1996; Wilson 2008). As a result, most have been limited to taxonomic identification and raw diversity estimates, precluding deeper paleoecological interpretation.

In this project, we extend our previous research on the taxonomy, taphonomy, and paleoecology of VMBs from classic localities in the Campanian Judith River Formation of Montana. Our new project will investigate a recently discovered VMB, the Turtle Hill site (Figure 2), in the Campanian-Maastrichtian Almond Formation of southwestern Wyoming (Flores, 1978; Roehler, 1988; Kieft et al., 2011; Rudolph et al., 2015; Lopéz et al., 2016). The Turtle Hill VMB is particularly significant because it represents a time interval that has been poorly sampled. It also provides an ideal opportunity to compare faunal diversity and depositional and taphonomic processes with the well-studied localities in Montana (Rogers 1995, 1998; Wilson 2008; Rogers and Brady 2010; Rogers et al. 2017; Roat et al 2019; Zimmermann et al 2019; Mendez-Curbello et al. 2022; Noonan et al 2022).

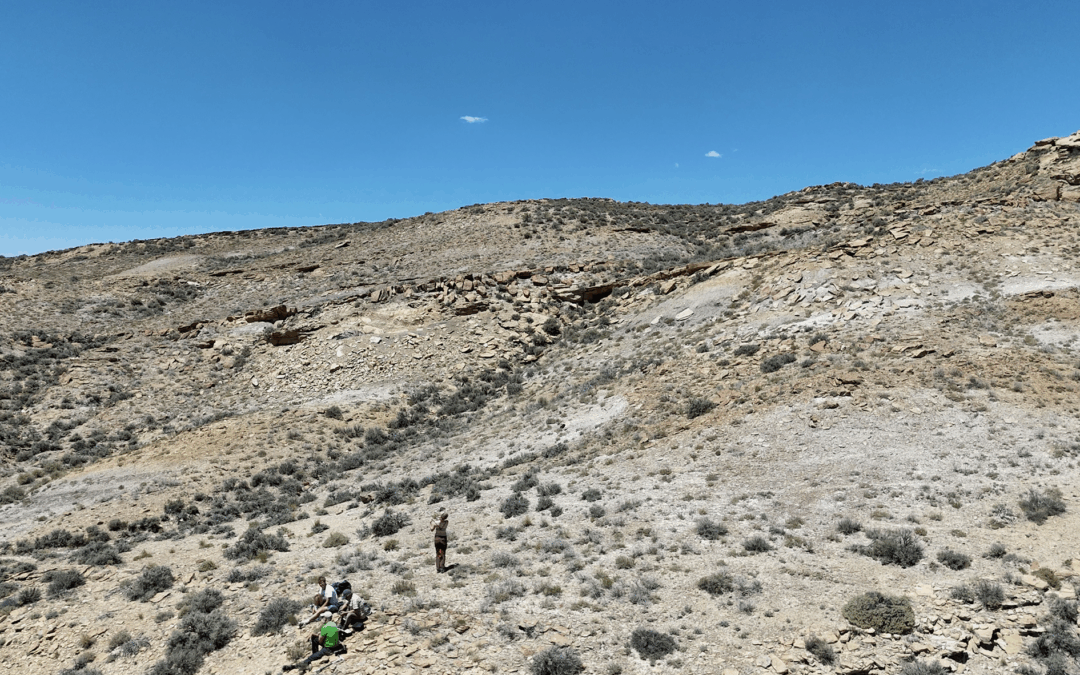

Figure 2: Almond Formation on Rock Springs Uplift. A) View of the well exposed Almond outcrop belt, which is ideal for logging section and prospecting for fossils. B) Macalester students measuring section through the Almond Formation in summer 2025. C) Numerous dinosaur sites have been recently documented in the Almond Formation, including a new bonebed that preserves at least one ankylosaur (Ethan Cowgill photo). D) View of the 2025 camp in the Almond Formation.

Field Area

We will go on an extended field excursion to the Almond Formation in southwestern Wyoming. The team will travel from Minneapolis-St. Paul (MSP) to Rock Springs, WY, then continue by 4WD vehicles to the field site, to meet our local collaborators. In the field, students will measure geological sections, prospect for fossils, help to excavate dinosaur bonebeds, and collect additional material from the Turtle Hill VMB. The field component will conclude with a visit to Dinosaur National Monument.

Skill Development

Students participating in this Keck Gateway Program will gain broad experience and foundational skills in:

- Fossil Identification: recognizing and classifying vertebrate, invertebrate, and plant fossils in the lab and the field.

- Fossil Collection Techniques: applying sampling protocols such as bulk sampling, surface collection, and larger-scale excavation of macrofossils.

- Sedimentary Geology: describing and interpreting common sedimentary rocks in the lab and the field.

- Analytical Methods: using petrographic and dissecting microscopes, SEM, and micro-XRF to analyze fossil material and sedimentary rocks.

- Field Methods: maintaining a field notebook, utilizing topographic maps and land ownership apps, recording GPS coordinates, prospecting for fossils, and measuring stratigraphic sections to contextualize fossil occurrences and marker beds.

- Collaborative Research: developing teamwork and problem-solving skills in the lab and the field.

- Scientific Communication: writing abstracts, creating posters, and presenting results at the annual Geological Society of America meeting in Denver, CO (October 2026).

Potential Student Projects

Student projects will directly contribute to the Project Directors’ ongoing research on VMB diversity and taphonomy. At the outset, students will work collaboratively to recover and identify vertebrate, invertebrate, and plant fossils from sieved bulk matrix collected at the Turtle Hill site currently stored at Macalester College (material will be permanently curated at the Museum of Natural History and Science at Cincinnati Museum Center). We will add data on sedimentology and stratigraphy, and potentially add new collections based on our work at the Turtle Hill locality during the field component of our project. Following the initial phase of fossil recovery and identification, students will work in pairs to describe, analyze, and interpret their fossil collections.

Project 1. Taxonomic characterization of the Turtle Hill VMB (4-6 students): Students interested in paleoecology and evolution will document the general biodiversity of the Turtle Hill assemblage. They will compile a general faunal list of identified taxa and compare this Campanian-Maastrichtian freshwater community from the Almond Formation with well-documented Late Cretaceous sites in Montana. We will test whether the Almond Formation collection is distinct from a faunal perspective from collections made in Montana.

Project Logistics

Students will arrive in Saint Paul, Minnesota, on June 10 and check into their Macalester College residence hall. The first week and a half will be spent in Macalester classrooms and laboratories, where students will be introduced to the project through a series of focused lectures, discussions, and hands-on experiences (e.g., fossil identification, basic vertebrate anatomy, sedimentary rock tutorial, methods of taphonomic characterization). In the lab, students will recover and identify fossils using dissecting microscopes and apply a range of analytical tools, including SEM-EDS and standard light microscopy, to study their collections.

On June 20, the team will travel to southwestern Wyoming to work in the outcrop belt of the Upper Cretaceous Almond Formation. We will camp onsite during this interval of the project. Students will gain diverse field experiences, prospecting and exploring new sites while developing essential field skills.

In the final weeks of the project we will return to the lab at Macalester to complete analyses, process our newly collected material, and prepare our GSA abstracts and posters. The goal is to have abstracts submitted and our posters largely completed before students depart on July 14.

Safety Issues

Fieldwork hazards: Summer fieldwork can be physically demanding and presents several risks: prolonged heat/sun exposure, long days and fatigue, travel on bumpy gravel roads and off-road hiking. All participants will receive field-safety training and are expected to follow field-appropriate dress including closed-toed shoes/boots.

References

Archibald, J.D. 1982. A study of Mammalia across the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in Garfield County, Montana. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 122:1286.

Blob, R.W. & A.R. Fiorillo. 1996. The significance of vertebrate microfossil size and shape distributions for faunal abundance reconstructions: a Late Cretaceous example. Paleobiology 22:422-435.

Brinkman, D.B. 1990. Paleoecology of the Judith River Formation (Campanian) of Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada: evidence from vertebrate microfossil localities. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 78:37-54.

Brinkman, D.B., D.A. Eberth, & P. J. Currie. 2007. From bonebeds to paleobiology: applications of bonebed data. In: R. R. Rogers, D. A. Eberth, and A. R. Fiorillo (eds.), Bonebeds: Genesis, Analysis, and Paleobiological Significance. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Brinkman, D.B., A.P. Russell, D.A. Eberth, & J. Peng. 2004. Vertebrate palaeocommunities of the lower Judith River Group (Campanian) of southeastern Alberta, Canada, as interpreted from microfossil assemblages. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 213:295-313.

Bryant, L.J. 1989. Non-dinosaurian lower vertebrates across the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in northeastern Montana. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 134:1-107.

Carrano, M.T. & J. Velez-Juarbe. 2006. Paleoecology of the Quarry 9 vertebrate assemblage from Como Bluff, Wyoming (Morrison Formation, Late Cretaceous). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 237:147-159.

Curry Rogers, K.A., and R.R. Rogers, 2024. Lost Worlds of the Dinosaurs. Scientific American 330 (February 2024 issue):28-35.

Demar, D.G., Jr., & B.H. Breithaupt. 2006. The nonmammalian vertebrate microfossil assembla ges of the Mesaverde Formation (Upper Cretaceous, Campanian) of the Wind River and Bighorn Basins, Wyoming. In: S. G. Lucas & R. M. Sullivan (eds.), Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. Bulletin of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science 35:33-53.

Dodson, P. 1971. Sedimentology and taphonomy of Oldman Formation (Campanian), Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta (Canada). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 10:21-74.

Dodson, P. 1987. Microfaunal studies of dinosaur paleoecology, Judith River Formation of southern Alberta. In P. J. Currie & E. Koster (eds.), Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosytems, Short Papers. Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology Occasional Paper 3:70-75.

Estes, R. 1964. Fossil vertebrates from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation eastern Wyoming. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 49:1-180.

Estes, R. 1976. Middle Paleocene lower vertebrates from the Tongue River Formation, southeastern Montana. Journal of Paleontology 50:500-520.

Estes, R., & P. Berberian. 1970. Paleoecology of a Late Cretaceous vertebrate community from Montana. Breviora 343:1-35.

Flores, R.M., 1978. Barrier and back-barrier environments of deposition of the Upper Cretaceous Almond Formation, Rock Springs Uplift, Wyoming. The Mountain Geologist 15:57-65.

Jamniczky, H.A., D.B. Brinkman, & A.P. Russell. 2003. Vertebrate microsite sampling: how much is enough? Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23(4):725-734.

Kieft, R.L., G.J. Hampson, C.A.-L. Jackson, & E. Larsen. 2011. Stratigraphic architecture of a net transgressive marginal- to shallow-marine succession: upper Almond Formation, Rock Springs Uplift, Wyoming, U.S.A. Journal of Sedimentary Research 81:513-533.

Koster, E. 1987. Vertebrate taphonomy applied to the analysis of ancient fluvial systems. Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists Special Publication:159-168.

Lillegraven, J.A., & J.J. Eberle. 1999. Vertebrate faunal changes through Lancian and Puercan time in southern Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology 73(4):691-710.

Lopéz, J.L., V.M., Rossi, C. Olariu, & R.J. Steel, 2016. Architecture and recognition criteria of ancient shelf ridges;an example from Campanian Almond Formation in Hanna Basin, USA. Sedimentology 63: 1651-1676.

Maas, M.C. 1985. Taphonomy of a late Eocene microvertebrate locality, Wind River Basin, Wyoming (USA). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 52:123-142.

Mendez-Curbelo, I., K. Nicolayevsky, M. Luft, R. Flowers, L. Zugschwert, K. Curry Rogers, & Rogers. 2022. Tracking paleonvironmental associations in vertebrate microfossil bonebeds in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Judith River Formation, Montana. Abstracts with Programs – Geological Society of America, 54(4).

Noonan, B., P. Lewis, B. Gomez, S. Esquenet, A. Jester, L. Rogers, K. Curry Rogers & R. Rogers. 2022. Tiny Modification features on fossil bones from vertebrate microfossil bonebeds in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Judith River Formation, Montana. Abstracts with Programs – Geological Society of America, 54(4).

Peng, J., A.P. Russell, & P.J. Brinkman. 2001. Vertebrate microsite assemblages (exclusive of mammals) from the Foremost and Oldman formations of the Judith River Group (Campanian) of southeastern Alberta: an illustrated guide. Provincial Museum of Alberta Natural History Occasional Paper 25:1-54.

Roat, G.E., S.P. Gomez, S.M. Tun, K.I. Irving, A.D. Lang, N.D. Clark, P.K. Zimmerman, K.R. Velasquez, R.R. Rogers, & K.A. Curry Rogers. 2019. Capturing a Late Cretaceous paleofauna: A new vertebrate microfossil bonebed in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Judith River Formation, Montana. Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, Paper no. 271-11.

Rogers, R.R. 1995. Sequence stratigraphy and vertebrate taphonomy of the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine and Judith River Formations, Montana. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago.

Rogers, R.R. 1998. Sequence analysis of the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine and Judith River formations, Montana: nonmarine response to the Claggett and Bearpaw marine cycles. Journal of Sedimentary Research 68:615-631.

Rogers, R.R. & M.E. Brady. 2010. Origins of microfossil bonebeds: insights from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of north-central Montana. Paleobiology 36:80-112.

Rogers, R.R. & S.M. Kidwell. 2000. Associations of vertebrate skeletal concentrations and discontinuity surfaces in terrestrial and shallow marine records: a test in the Cretaceous of Montana. Journal of Geology 108:131-154.

Rogers, R.R., K.A. Curry Rogers, B.C. Bagley, J.J. Goodin, J.H. Hartman, J.T. Thole, & M. Zatoń. 2018. Pushing the record of trematode parasitism of bivalves upstream and back to the Cretaceous. GEOLOGY 46: 431-434.

Rogers, R.R., K.A. Curry Rogers, M.T. Carrano, M. Perez, & A. Regan. 2017. Isotaphonomy in concept and practice: an exploration of vertebrate microfossil bonebeds in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Judith River Formation, north- central Montana. Paleobiology 43:248-273.

Rogers, R.R., S.M. Kidwell, A. Deino, J.P. Mitchell, & K. Nelson. 2016. Age, Correlation, and Lithostratigraphic Revision of the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Judith River Formation in its Type Area (north-central Montana), with a Comparison of Low- and High-Accommodation Alluvial Records. Journal of Geology 124:99-135.

Rudolph, K.W., W.J. Devlin, W.J., & J.P. Crabaugh. 2015. Architecture and recognition criteria of ancient shelf ridges; an example from Campanian Almond Formation in Hanna Basin, USA. Mountain Geologist 52:13-132.

Sahni, A. 1972. The vertebrate fauna of the Judith River Formation, Montana. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History Museum 147:321-412.

Sankey, J.T. 2001. Late Campanian southern dinosaurs, Aguja Formation, Big Bend, Texas. Journal of Paleontology 75:208-215.

Sankey, J.T. & S. Baszio (editors). 2008. Vertebrate Microfossil Assemblages: Their Role in Paleoecology and Paleobiogeography. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Simpson, G. G. 1926. The fauna of Quarry Nine. American Journal of Science, series 5 12:1-11. Sloan, R.E. 1969. Cretaceous and Paleocene terrestrial communities of western North America. Proceedings of the North American Paleontological Convention, Part E: 427-453.

Sloan, R.E., & L. Van Valen. 1965. Cretaceous mammals from Montana. Science 148:220-227.

Wilson, L.E. 2008. Comparative taphonomy and paleoecological reconstruction of two microvertebrate accumulations from the Late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation (Maastrichtian), eastern Montana. Palaios 23:289-297.

Wolff, R.G. 1973. Hydrodynamic sorting and ecology of a Pleistocene mammalian assemblage from California (U.S.A.). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 13:91101.

Wood, J.M., R.G. Thomas, & J. Visser. 1988. Fluvial processes and vertebrate taphonomy: The Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation, south central Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 66:127-143.

Zimmermann, P.K., A.D. Lang, G.E. Roat, K.R. Velasquez, S.M. Tun, K.I. Irving, S.P. Gomez, N.D. Clark, K.A. Curry Rogers, & R.R. Rogers. 2019. Taphonomic comparison of vertebrate microfossil bonebeds from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River and Hell Creek formations of Montana. Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, Paper no. 38-23.